The Rankins of Cherry HillStruggling with the Loss of Their World

Cherry Hill was home to Catherine Putman Rankin and her family from 1884 through 1963. Within its walls, Catherine created a refined way of life that glorified her Van Rensselaer family heritage. During her lifetime, she and other members of America's elite faced profound social, economic and political changes that threatened their way of life and position in society. Catherine and many others chose to look to the past as a means of coping with these changes.

"When I was a very little girl I used to think that the stars were the windows of heaven and at each window was an angel and the largest and brightest star I thought was the window my dear momma was at. Shall we too leave the world and be forgotten as the clouds vanish from my view? And the lilies, and the daisies and the flowers Of the brightest hue, all must pass away." Catherine "Kittie" B. Putman, 1871, Age 14

Catherine Putman's life was marked by unsettling change, both personally and in the larger world around her. That Catherine was directly descended from the prominent 18th century Van Rensselaers became critically important in her life.

The 18th Century Van RensselaersAmerican Aristocrats

The Cherry Hill Van Rensselaers were part of a group of wealthy and powerful families known as the Hudson River manor lords.Under Dutch rule, which lasted from 1624 to 1664, the Dutch West India Company and the States General of the Netherlands granted vast expanses of land--or patroonships--to members of the company who could establish and populate settlements in the colony. Kilian Van Rensselaer (1585-1646), a Dutch merchant and the founder of the dynasty to which generations of Cherry Hill occupants belonged, was one such individual. His roughly 850,000-acre tract, called Rensselaerswyck, was the only patroonship to be successfully established during the Dutch period. The English who took over the colony in 1664 patented a larger (one million acres) Rensselaerswyck and went on to establish about 30 more estates--14 with lordship privileges--occupying more than two million acres.

Eighteenth century Hudson River manor lords grew in wealth and power. Like other elites in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore, they engaged in lucrative trading enterprises. The Hudson River families also derived wealth and status from renting their enormous landholdings. Many Hudson River settlers were tenants on these manors--they did not own the land. The English, like the Dutch before them, gave the lords feudal powers--judicial and administrative--over their tenants. Although the judicial and administrative powers were soon removed by the New York General Assembly, the lords maintained extensive power derived from their wealth-producing land and the feudal-like leases they offered. But the feudal rights, short lived as they were, gave them an aura that approximated the Old World aristocracy.

Of course, American elites were never true aristocrats. They were not titled families--lords and counts and dukes. But their wealth and social status that went along with it gave them the needed credentials to qualify as an American version of the real thing. So too did one other essential ingredient of aristocracy-- refinement, the visible expression of their class. American aristocrats were regarded as a better sort of people because they disciplined themselves to live a structured life based on manners and virtue. Their goal was to perform perfectly amidst beautiful surroundings. Exquisitely outfitted, they lived in large houses surrounded with beautiful things. They danced, dined, drank, talked, and played cards with elegance and restraint, rather than with what they viewed as the riotous excess and crude manners of those below them. Refinement required taste, but it also required leisure time--for ladies to indulge in ornamental needlework, for gentlemen to learn Latin. This concept of refinement was a key element of aristocracy that would have major influence on generations of Van Rensselaer descendants.

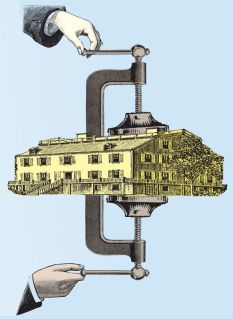

Feeling the SqueezeBy the late 1800s, there existed a class of new millionaires with unprecedented levels of wealth.

Major economic changes brought new sources of wealth through banking, land speculation, canals, railroads and manufacturing. While some older elites invested in these enterprises, many did not keep pace and were soon outdistanced by new entrepreneurs. At Cherry Hill, the family's fortune was in trouble as early as the 1820s. Such families as the Whitneys, Vanderbilts and Morgans made vast fortunes in railroads, finance and heavy industry. Their way of life stood in direct contrast to the refined existence of the old families. Their New York City mansions and Newport cottages typified their excess and ostentation. Families like the Van Rensselaers would have considered these new millionaires to be vulgar in their taste and ostentatious display of their wealth.

There were no Whitneys, Vanderbilts or Morgans in Albany. Instead, new banking, railroad, and industrial empires were being built in cities such as New York, Pittsburgh, Buffalo and Chicago. The new economy seemed to pass by Albany. This may have seemed an insult to the Van Rensselaers, who had considered themselves to be part of a national elite. Albany's decline threatened to reduce families like the Van Rensselaers to the status of a merely local elite.

At the same time, the old Albany families and others like them faced challenges from those below them on the social and economic scale. Urban populations changed dramatically after 1890. Unprecedented numbers of Jewish, Catholic and Eastern Orthodox immigrants fled economic, political and religious persecution in Europe. Welcomed by some as a source of cheap labor, they faced discrimination from the older immigrants from England, Germany, Ireland and Scandinavia. Mainly settling in cities, they became important sources of votes for urban political machines, much to the dismay of the elites. And in the 1910s and 1920s, millions of African Americans migrated to northern cities. In Albany, they joined an older black community that traced its ancestry to the Hudson River Valley slaves of the 1700s. Albany's South End, where Cherry Hill is located, became home to African Americans, Germans, Italians, and Jews from Eastern Europe by the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

By 1876, evidence of industrialization surrounded Cherry Hill. Workers' houses, along with an icehouse and a brewery, were next door. And just beyond the front gate was the noise and dirt of the Albany & Susquehanna Rail Road and the Olcott Iron Manufacturing Company.

During this time of enormous change, anti-immigrant, antiblack, anti-Catholic, and anti-Semitic sentiments were common among American elites. Threatened by their growing economic and political power, native born, old-stock Americans perceived these new populations as a moral and political threat to America, and unfairly labeled them as lazy, depraved and crude--as unrefined. Such sentiments underlay the movement to restrict immigration, culminating in the National Origins Acts of 1921 and 1924. This legislation established quotas of immigrants from each country, and the quotas were deliberately set to welcome immigrants of some ethnic backgrounds-- northern Europeans--and to exclude others--southern and eastern Europeans. It was also during this period that women's suffrage was on the national agenda. Many women from these old families, politically conservative in their upbringing, were ardent anti-suffragists. Because their political loyalties were tied so closely to their class identity, they would have thought it unacceptable to extend the right to vote to working class and immigrant women.

For families like the Van Rensselaers, the challenges they faced from both the new millionaires and new immigrants were not that different--they were feeling squeezed from two directions. Both groups--the new millionaires from above, and the rising immigrant class from below--took away power and standing that had once belonged to the older American aristocracy. Frightened of becoming powerless and, even worse, irrelevant, these older aristocrats needed to prove they still had some basis for social and cultural authority, something no other group could claim. That something was their colonial lineage. Along with it came the refinement associated with the lives of the colonial aristocracy. Neither money nor numbers could buy real class, they claimed--their history was both beyond challenge and unavailable to newcomers.

This pride in lineage spawned a fascination with tracing one's ancestry. Older aristocratic families founded hereditary organizations like Daughters of the American Revolution, Colonial Dames of America, The Order of Colonial Lords of Manors in America, United States Daughters of 1812, and Sons of the American Revolution. These patriotic organizations were all exclusive, and to gain membership, one had to be able to trace one's lineage to service in the wars or earliest Dutch and English settlement in North America. These same families socialized at exclusive clubs. In Albany, these included the Fort Orange Club and the University Club. Nationally, many of these clubs excluded those who did not have the proper lineage, including Catholics, Jews and African Americans. In Albany, the Fort Orange Club excluded African Americans until 1977. While an 1880 founding member of the club was Jewish, there was a long period through the mid-20th century during which no new Jewish members were admitted--until 1967.

A Disappearing Class Reacts

Old Albany families included names like Pruyn, Sanders, Lansing, Schuyler, and of course, Van Rensselaer. In response to the major changes that were occurring in Albany's population, economy, and politics, many of these families looked to the past, and they actively preserved and restored their landmarks, including Schuyler and Ten Broeck Mansions, and Crailo, located just across the river. These grand old homes drew national attention as symbolizing an older and better way of life. Cherry Hill was just one such house to be featured in books, magazine articles and museum exhibitions devoted to the colonial period.

Aristocrats like Catherine Rankin also looked to the values of the past, recalling a time before either the vulgar rich or the vulgar poor held power. They celebrated the colonial era as a time of restrained elegance, in sharp contrast to what they regarded as the ostentation of the new millionaires and the coarseness of the new immigrants. This was the message of Cherry Hill as physically shaped by Catherine's presence and vision.