The Solomon & Arriet Van Rensselaer Collection

Second Generation: 1774-1852

Arriet Van Rensselaer (1775-1840), daughter of Cherry Hill’s original owners (Philip and Maria Van Rensselaer), married her first cousin, Solomon Van Rensselaer (1774-1852) in 1797. The couple at first split their residence between an Albany townhouse and a property called “Mount Hope,” which was broken off from the original 900-acre Cherry Hill estate. After the deaths of both of Arriet’s parents around 1830, she and Solomon came into ownership of Cherry Hill itself.

Solomon, following in his father’s and grandfather’s footsteps, enjoyed a prominent military and political career. He was General Stephen Van Rensselaer’s chief advisor in the War of 1812, Adjutant General of the New York Militia, and a U.S. Congressman from 1818-1821. The social and political transformations of the Early Republic, however, often left Solomon wanting for economic stability, and his career, which kept him for long periods from his family, often left them wanting for his company.

Solomon and Arriet’s papers reveal a family in society’s upper echelon—but struggling desperately to retain their place there. Their letters describe New Year’s Day festivities, visits from Governor and Mrs. DeWitt Clinton, and attendance at a grand ball celebrating the opening of the Erie Canal in New York City. Yet Arriet’s accounts of her prodigious butter- and cheese-making operations and her children’s letters pleading that both parents desist from working so hard suggest nothing close to a life of leisure. The collections associated with Solomon and Arriet’s household reflect both aspects of the family’s experience.

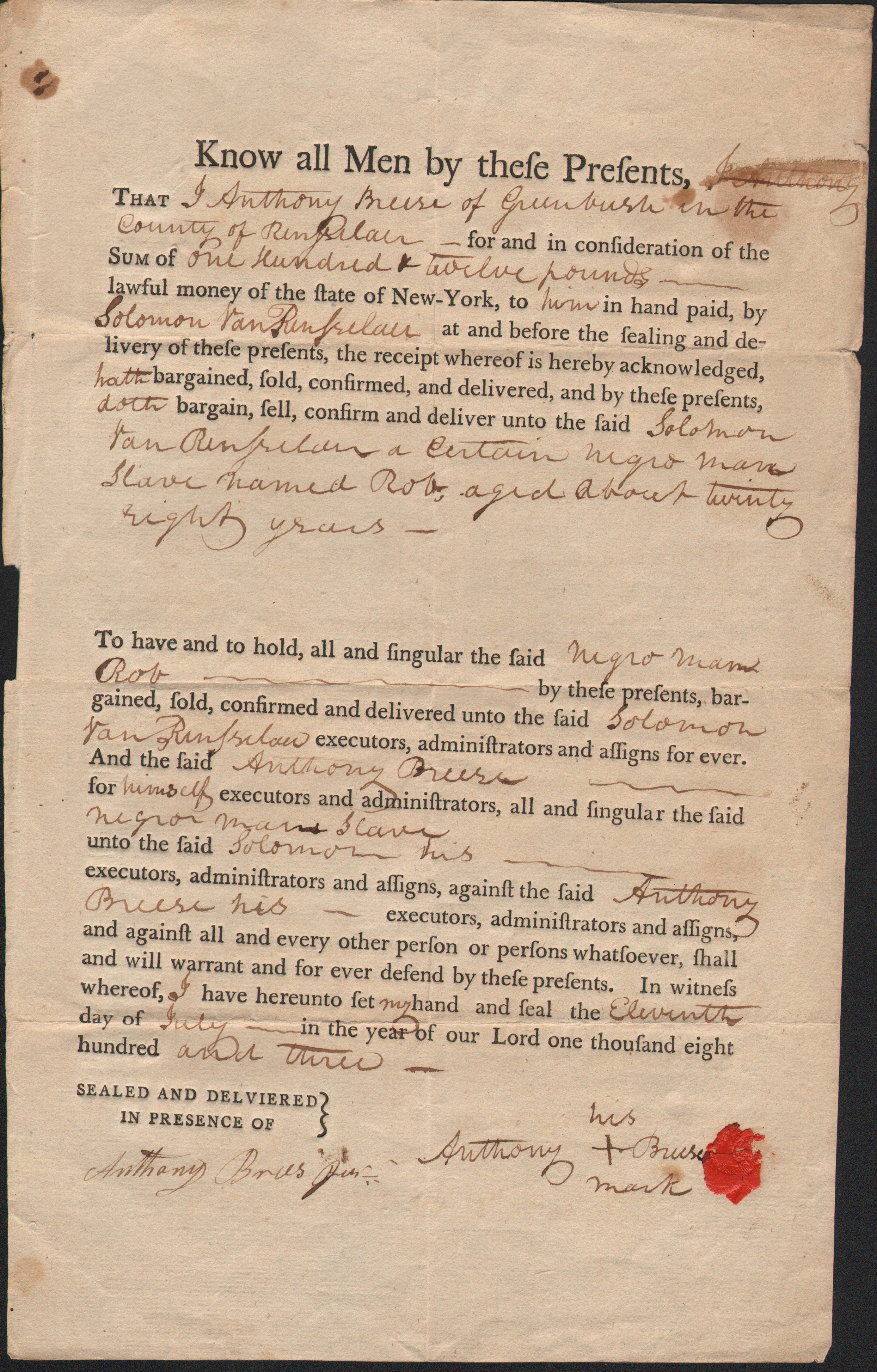

The Solomon and Arriet Papers also document the family’s continued reliance on the labor of enslaved people right until 1827 when slavery ended in New York. The papers provide insights into a second line of descent at Cherry Hill: that of Dinah Jackson, also known as “Dean” who came to Cherry Hill in 1803 as an enslaved cook; her daughter, Dian, who was indentured to Solomon under Gradual Abolition laws; and Dian’s daughter, who was born in the household of Solomon Van Rensselaer. Other family papers tell us that Dian’s daughter was Jane Jackson Knapp whose children, William James, Jame Amelia, Richard, and Harriet Maria “Minnie” Knapp, were raised as wards and servants at Cherry Hill and other Van Rensselaer households

Painting

Ezra Ames

Oil on Canvas

1819

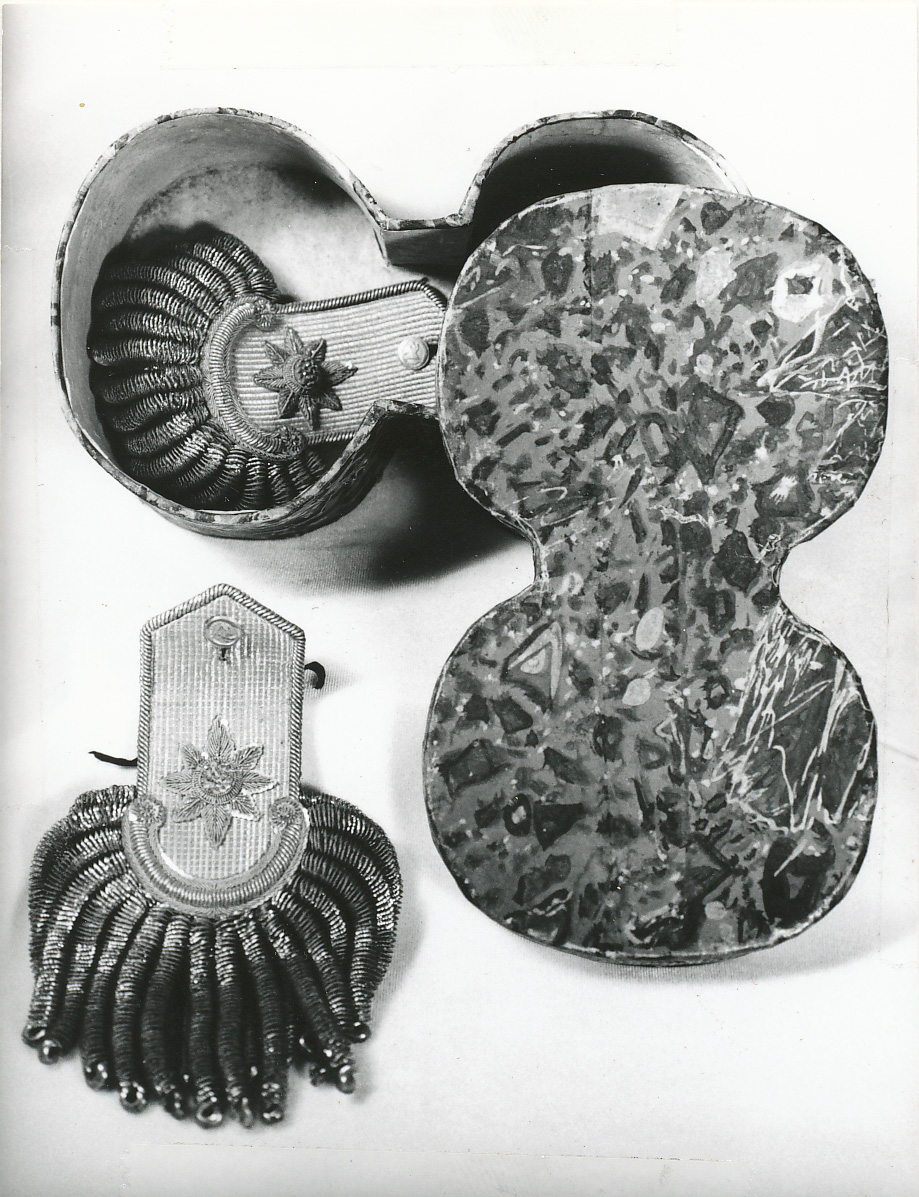

This portrait depicts Solomon Van Rensselaer at the height of his career. He had recently been appointed to the office of Adjutant General and won a seat in Congress representing the Albany District. The epaulets that Solomon wears remain in the Historic Cherry Hill collection today.

Albany portraitist, Ezra Ames painted many prominent individuals—including Alexander Hamilton and Martin Van Buren. Roderic Blackburn notes that Ames recorded this portrait in his account book on December 6, 1819, charging for the painting and for the “Burnished gilt frame.” Another Ames portrait of Solomon, now lost, was commissioned for a gallery of “Distinguished Americans” in Philadelphia.

Painting

Frederick Fink

Oil on Canvas

1840

Arriet Van Rensselaer is portrayed holding spectacles and a Bible open to Psalm 9. According to Emily Rankin’s 1941 record of a family tradition, the portrait was painted posthumously: “She was very lovely but refused to have her portrait painted and her husband said if he had to wait till she was dead he would have a portrait of her and he did.” The props in the painting were likely chosen very deliberately by the family to commit their loved one to memory. The clear depiction of the Bible open to a particular Psalm may suggest that that passage was meaningful to Arriet.

Fire Screen

Arriet Van Rensselaer

Silk on Canvas

1793

Albany

Collection of the Albany Institute of History & Art

This fire screen includes a needlework panel worked in Queen’s stitch and signed in needlework, “Arriet Van Rensselaer 1793.” The Cherry Hill family donated the firescreen to the Albany Institute of History & Art in 1954, and it is currently on long-term loan to Historic Cherry Hill.

Tea Set

Boyce & Jones

Silver

c. 1825

New York

Originally made in New York City by Boyce and Jones, Solomon purchased this tea set from Albany silversmiths Shepherd and Boyd in 1826. Some of the pieces bear the marks of both shops, and a receipt in Solomon’s papers records the sale. Shepherd and Boyd were apprentices of Albany silversmith Isaac Hutton (1766-1855). The Cherry Hill collection includes pieces by Hutton, Shepherd and Boyd, and successive partnerships, Boyd and Wendell, and Wendell and Mulford, indicating a multigenerational patronage of a lineage of Albany silversmith shops.

This set includes a teapot, cream pot, sugar bowl, and slop bowl, each bearing the conjoined monogram “SAVR” for Solomon and Arriet Van Rensselaer. The considerable number of silver pieces in the Cherry Hill collection associated with Solomon and Arriet suggest their elite status.

Dress

Silk satin and silk gauze

c.1825

This early nineteenth-century gown was probably made for one of Solomon and Arriet Van Rensselaer’s daughters, and it may have been worn at a ball in New York City celebrating the opening of the Erie Canal. In a letter dated October 26, 1825, Arriet wrote from New York to her family back at Cherry Hill about the spectacular ceremony celebrating the canal’s opening. While Solomon and their daughters continued on to the ball, Arriet stayed behind to write her letter home (and perhaps enjoy some rare peace and quiet). The satin and silk gauze gown is embellished with a chain motif that may represent the Erie Canal “linking” New York to the west.

Stocking

Silk

Early 19th century

What’s in a sock? Perhaps a great deal at a closer look. This silk stocking belonged to Arriet Van Rensselaer of Cherry Hill during the early nineteenth century. It features embroidery and openwork decoration only on its lower section, so that a lovely ankle glimpsed beneath a long skirt might be elegantly embellished. The decoration and silken fabric reflect Arriet’s well-to do status—but a close look at the stocking’s many mends and reinforcements gives us a sense of household economy as well as the value of textiles. Even in an elite household, stockings might be well worn and repeatedly repaired.

The top of the stocking is inked with the initials “AVR.”

Epaulets in Box

c. 1820

These epaulets bear the single star of a Brigadier General and the button (an eagle arising from a half globe) of the New York State Militia. Solomon wears these epaulets in his portrait painted in 1819 by Ezra Ames.

Hot Water Plate

Porcelain

c. 1800

China

The set of octagonal hot water plates pictured here bear the typical blue-and-white design of Canton ware. Hot water could be added to the interior of the plate through a small opening on the side to keep food warm. This plate may be among the items included in the 1852 inventory of Solomon Van Rensselaer’s estate: “1 blue China Dinner Sett.”

Bill of Sale

Between Anthony Breese and Solomon Van Rensselaer

1803

This document is a bill of sale documenting Solomon Van Rensselaer’s purchase of an enslaved man of 28 years named Rob. However assiduous Solomon and Arriet may have been in their respective labors—Solomon in his career and Arriet in her oversight of household operations and production—there can be little doubt that the hardest labors were endured by the enslaved men and women in the Van Rensselaer household who enjoyed little of the reward. Solomon opposed the extension of slavery into new territories, yet he himself owned slaves well into the waning years of that institution in New York.